13 MINUTE READ

Mizoram, an underappreciated jewel in India’s northeast, has a wonderful thread of history and culture that is exquisitely depicted by its historic monuments. As we travel around this wondrous region, we come across tangible traces of history that serve as evidence of the people’s tenacity and artistic talent.

Mizoram’s cultural landmarks, which range from old watchtowers guarding the hills to finely crafted churches that merge architectural splendor with spirituality, clearly depict its heritage. Get ready for a trip through historical and artistic areas as we explore the significance of Mizoram’s landmarks and their part in preserving the state’s heritage.

Enjoy reading!

To Start with Some Background!

Mizoram comprises two Mizo phrases: Mizo and Ram. ‘Mizo‘ is the locals’ endonym, while ‘ram‘ means ‘land‘. Thus, “Mizoram” means “Mizo land” or “land of the Mizos“.

Mizoram is in northeastern India, having Aizawl serving as the capital and the main city. It is the southernmost state in India’s northeast, sharing boundaries with three of the Seven Sisters States, Tripura, Assam, and Manipur, as well as a 722-kilometer border with Bangladesh and Myanmar. The state covers roughly 21,087 square kilometers, with around 91% of the land being forested. It is the country’s second least populous state, with an expected citizenry of 1.25 million in 2023.

The Village and Building Types of Mizoram

How does a Traditional Mizo Village (Zokhua) look like?

The Mizos constantly emigrated from one location to another in quest of better jhum land, as jhuming needed shifting cultivation sites. A typical Mizo hamlet was a flurry of activity. The settlement was often located atop a hill and consisted of a bunch of bamboo huts on stilts. It was made up of around three to five hundred dwellings in total, with the chief’s elongated hut in the center, surrounded by the village elders’ houses. And nearby was the enormous, hump-roofed Zawlbuk, or bachelor’s dormitory, where all the young men gathered at sunset and slept. This was a hub from which to gather news or summon help in an emergency.

It also served as a training ground for Mizo boys, where they were taught and molded to be responsible members of society. Other notable figures included Puithiam, a priest, Thirdeng, a blacksmith, and Tlangau, a crier. Though wealthy men, valiant warriors, and hunters held high status, there was virtually no social discrimination. As a gregarious and close-knit society, they developed ideals of self-help and cooperation to meet societal obligations and responsibilities. The Mizos formed a distinctive code of ethics known as Tlawmngaihna, which essentially stands for unselfish devotion to others. It is a powerful moral force that needs a man to be welcoming, compassionate, selfless, brave, and beneficial to others.

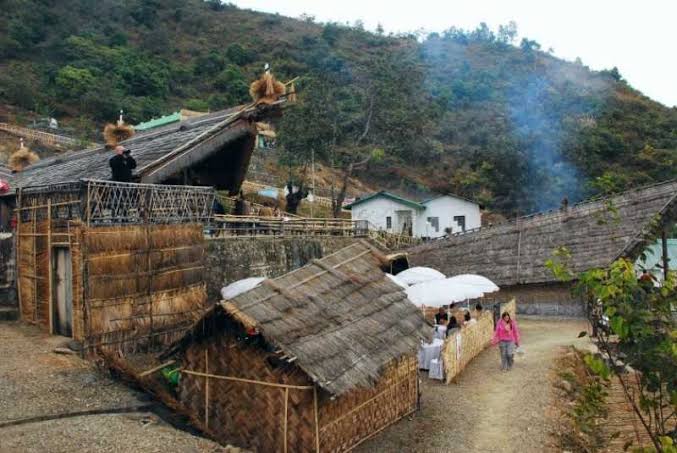

The Falkawn Village

Falkawn is a modest village 18 km south of the primary city of Aizawl. Tourists throng this attraction, which depicts the lifestyle and traditions of a typical Mizo hamlet.

The Social Hierarchy and Institutions of Mizoram

Whilst social hierarchy existed in the early Mizo community, it was not rigid. In terms of organization, there was minor variance in the different areas; the sequences were as follows:

- Lal (Chief) or the Royal Family

- Upa (elders or ministers to the chief)

- Ramhuals (stellar jhum cultivators).

- Zalens (people who are excluded from giving fathang or paddy tax to the chief).

- Puithiam (priest) and Thirdeng (blacksmith)

- Bawis (people who are forced to seek refuge at the chief’s home).

- Hnamchawm (Commoners)

In the Mizos, the father is the head of the household. He possesses control over the property, as descent is patrilineal. The offspring would take the name of their father’s clan.

The Zawlbuk

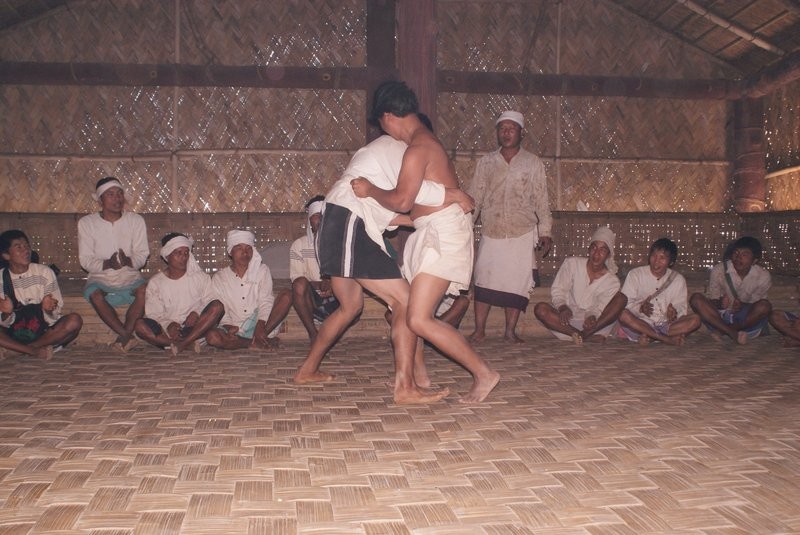

The villagers expected unmarried and newly married young men over the age of fifteen to sleep in the Zawlbuk, a large house also known as a bachelor dormitory. The dormitory is situated in the open space at the village’s highest point, opposite the chief’s residence. The village elders, known as Upas, dwell nearby. The zawlbuk is composed of timber with bamboo, with a roof of thatch and an upward deck of rough logs to approach the entrance. A hearth filled the center of the dorm hall, and a raised platform to sleep on stretched from the far end across the room. People used the open space around the hearth as both a wrestling ring and a dance floor. The zawlbuk operated as both a rest house for community guests and a place for single teenagers to sleep.

The Commoner’s House

The commoner’s house is divided into three sections: the front verandah, which was accessed via a rough log platform, the main chamber, and a tiny room partitioned off at the other end, behind which there was occasionally a little bamboo platform. The verandah was named ‘sumhmun‘ for the ‘sum’ or mortar used to pound paddy, which was located there.

The careful housewife placed her firewood on one side, and the front facade of the house was where the householder, if he is a skilled hunter, displayed the skulls of the birds and animals that he had shot; among them hung baskets in which the fowls laid and even sat on their eggs, hatching out as many and healthy broods as the most pampered residents of model poultry farms. The birds spend the evenings in long tabular bamboo baskets suspended beneath the eaves, which they reach by climbing a slanted stick from the front porch. Brooding chickens were kept each night in one-of-a-kind baskets with sliding doors.

A small door, about two and a half feet by four feet, with a very high sill, opened into the house from the verandah. The door was placed on the side furthest from the hill and consisted of a strip of split bamboo work connected to a long bamboo that slides to and fro, lying in the groove within two other bamboo struck atop the sill, where there was a small opening, with a swaying door, for use by the dogs and fowls if the big door was closed. Immediately inside the entrance, in one corner, were the hollow bamboo tubes that replaced the water pots; on the opposite side was frequently a large round bamboo bin housing the household’s paddy supply.

Khum-ai, or a sleeping platform, came next. Beyond that was a mud hearth in the center with three stones or iron pieces attached where the cooking post rested. The soil was held in place by three pieces of wood, the first being a wide plank with a nicely sanded top that served as a pleasant seat during cold weather. The earth was damp and well-kneaded before hardening to the consistency of brick. Along the wall, an earthen shelf serves the dual goal of keeping the fire away from the wall and providing a resting area for the pots. They hung two bamboo shelves over the hearth, one above the other, to dry future paddy supplies and store miscellaneous odds and ends.

These shelves also helped to prevent the flames from hitting the roof. Beyond the fireplace was another sleeping area known as the Khum-puii, or the huge bed, which was meant for the parents, while younger kids and unmarried girls utilized the Khum-ai, and bigger lads and young men, formerly said, slept in the zawlbuk. Beyond the Khumpui was a divider that separated the small alcove used as a lumber room and, more commonly, a closet.

The Chief’s House

The chiefs’ residences (known as Lal) were quite similar to the commoners’ houses. Stepping into the main verandah, the guest finds himself in a corridor running across one side of the residence, off which opened a variety of rooms resided by the married keepers; the other side of the passage popped into a large room containing multiple sleeping platforms and, on occasion, two or more hearths, but if not similar to the one described above.

Beyond there was the typical closet, as well as a large verandah that was partially walled in and reserved exclusively for the chief’s family. The verandah known as “Bahzar” was banned to everybody but the chiefs or affluent individuals who had given specific feasts.

A similar limitation applies to windows, which were among the Thangchhuah’s prerogatives. The villagers viewed openings on the side of the home with distrust, believing that they would bring disaster. In the most progressive cases, they disregarded the strong public sentiment that such an invention would harm the whole village.

What is the Settlement Pattern in Mizoram?

Human settlement formed a pattern and structure that had a significant impact on the villagers’ lives and livelihoods (Chitambar, 1997). The villagers in the study village constructed dwellings from wood and bamboo on the top and slope of the hill along the road. Houses built on the hillside had a base of wooden pillars that ran parallel to or a little higher than the roadway. Traditionally, Mizo buildings were rectangular, with a thatched roof (Di, or straw), walls built from weaved bamboo or timber framework, and a bamboo mat floor. However, there were no such houses in the village today.

The thatched roof was replaced with a tin roof, the weaved bamboo walls with tiles, and the bamboo mat floor with hardwood planks.

The majority of the dwellings in the village were Assam-style, with a few cement-concrete buildings and only a handful built of traditional bamboo walls with tin roofs.

When the villages were within the jurisdiction of chiefs, their numbers and names changed frequently. People were always looking for farmland and water. The chiefs also divided up the villages among their sons. A historic settlement atop the hills’ spur was shapeless and crowded. In 1966, the authorities implemented a project called “Operation Security,” which involved 68 percent of the population and aimed to reconstruct communities.

These new communities are of the linear cluster form, with a main road bisecting each town and all smaller lanes radiating from a main square, with dwelling groups positioned along the roadsides. Each community features a minimum of one church, a public school, a blacksmith shop, and a few shops. Villages consist of 60 to 80 dwellings and have an average population of 400 to 700. Houses are built on elevated bamboo or wooden poles. There are two sorts of houses: two-sided roofs and four-sided roofs. A typical average dwelling is rectangular, with a two-sided thatched roof. Split or plaited bamboo makes up the floor and side walls, which have one or two windows.

The well-off utilize timber planks for the floor with corrugated iron for their roofs. Typically, the well-off build an earthen hearth toward the left side of the roof’s center. In traditional homes, the owner of the house sleeps in the main bed at the back of the fireplace. The huge space is also partitioned into cubicles to provide seclusion. Grains and food are stored in a corner of the space. The poultry and pigs are housed either on the front verandah or in an enclosed space behind the house.

Major Buildings and Places in Nagaland

1. Solomon’s Temple

Solomon’s Temple is a shining treasure in Mizoram’s cultural landscape. The Temple’s magnificence is a great example of architectural creativity and spiritual commitment beyond its function as a holy sanctuary. As the sun shines its golden rays on the Temple’s ornate exterior, a rush of color emerges, representing faith, innovation, and cultural identity.Although Christianity is prevalent in Aizawl, there is also a temple. Hindus from other regions of India should see the spot. Shiv Mandir is a temple in Zotlang, a lovely neighborhood in the western section of Aizawl. The Gorkha Hindu followers built Shiv Mandir, the temple in Zotlang, a lovely neighborhood in the western section of Aizawl, as old as the locality formerly referred to as Shri Mantilla. The local Gorkha population maintains it. The Shiv Mandir has a unique history. To approach the mandir, one climbs a flight of stairs from the alley, which is roughly three floors above the road level. This location has its distinct character, and the Pindi is very appealing. This site offers an overhead perspective of the eastern half of Aizawl.

2. Mizoram State Museum

The Mizoram State Museum is a legacy repository that links Mizoram’s modern identity to its historical foundations. The delicate threads of the state’s varied ethnicities and customs are meticulously intertwined inside its walls. From the bright costumes of several Mizo tribes to antiques demonstrating the growth of local skill, the museum captures the essence of Mizoram’s culture.

3. Reiek Tlang

Reiek Tlang, perched over the emerald vastness of Mizoram’s scenery, invites inquisitive travelers to uncover its mysterious history. A symphony of rock and nature resounds among the ruins of an ancient fortress, a tribute to time and the stories it holds. As footprints echo across the stones, they connect with the lives and dreams of individuals who once sought safety beneath these walls.

Reiek Heritage Village is a glimpse into the essence of Mizoram, with handcrafted huts that highlight traditional architectural genius and exuberant events that honor age-old customs.

4. Mizo Hlakungpui Mual

Mizo Hlakungpui Mual is a poignant memorial to the unshakable heroism and sacrifice of Mizo troops who served during World War I. Nestled in the heart of Mizoram, this evocative memorial serves as an emblem of the region’s contributions to the history of humanity.

The edifice, distinguished by its beautiful architecture and tranquil setting, evokes a sense of reverence and introspection.

5. KV Paradise

KV Paradise, located in the gorgeous surroundings of Champhai, Mizoram, is a location where joy takes center stage. This charming amusement park has earned the reputation of being a haven of laughter and thrill among locals and tourists. With exhilarating rides, engaging shows, and a kaleidoscope of shades, KV Paradise invites guests of all ages to feel unbounded joy.KV Paradise, located in the gorgeous surroundings of Champhai, Mizoram, is a location where contentment takes center stage. This charming amusement park has earned the reputation of being a haven of laughter and exhilaration among locals and tourists. With exhilarating rides, engaging performances, and a kaleidoscope of hues, KV Paradise invites guests of all ages to feel unbounded joy.

6. Zion Street

Zion Street is more than simply a roadway; it’s a live portrait of Aizawl’s culture, history, and daily life. Walking down this lively street, one hears the chatter of residents, smells the perfume of local cuisine, and witnesses the bustle of trade, creating a symphony of noises. The street’s unique mix of businesses, cafes, and vendors exemplifies Mizoram’s dynamism, where tradition coexists peacefully with modernity. Zion Street’s antique buildings, embellished with vivid paintings, tell stories of earlier days while embracing the spirit of today.

7. Tomb Of Vanhimailian

The Tomb of Vanhimailian is a moving tribute to a beloved Mizo chief. This monument captures the essence of a man who helped shape the region’s history.

The tomb’s calm surroundings and artistic architecture highlight Vanhimailian’s services to the Mizo community. This mournful memorial reminds visitors of the sacrifices and aspirations that shaped Mizoram’s journey.

8. Baktawng Village

Beckons entice interested travelers with their distinct appeal. Aside from its green landscapes and peaceful atmosphere, the community is famed for housing the world’s largest family. The unique architecture of their traditional residences exemplifies the village’s social fiber of unity and belonging. Walking through Baktawng’s alleyways, tourists can see the harmonious integration of heritage and modernity, where traditional rituals combine smoothly with current lines.

9. Lianchhiari Lunglentlang

Located in Duntlang village, the cliff has a dangerously long, rocky protrusion. A person may spend several hours sitting on the granite ledge, enjoying the fresh breeze.

10. Fiara Tui

It is situated in Champhai. The spring has a particular place among the Mizos because of the delicacy and purity of its water, which is described in many of their texts and traditions.

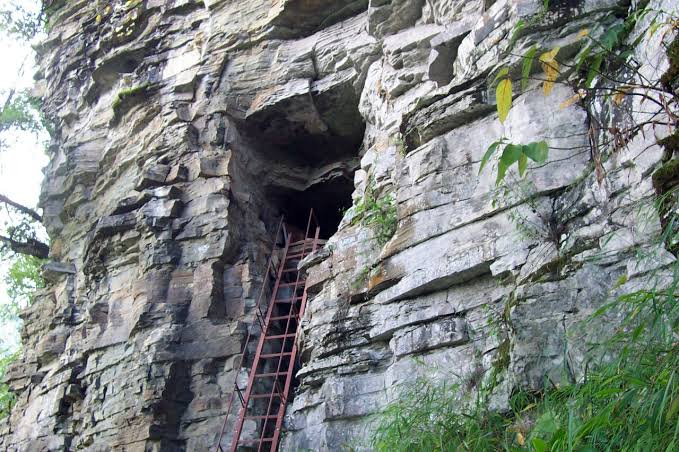

11. Lamsial Puk

Located in Farkawn village, this cave’s significant feature is a wooden box that stores approximately a cubic meter of firmly packed and highly preserved human bones.

12. Chawngvungi Lungdawh

Chawngvugi Lungdawh is located in Khankawn village. There are several archaeological sites and relics in the city and its surrounding area. This city boasts an enormous monolith (about 25 feet).

13. Sibuta Lung

It is a tribute stone in Tachhip village, built by a Palian chief approximately 300 years ago. The memorial of Sibuta Lung tells a story of betrayed love and the need for vengeance.

14. Khuangchera Puk

The Khuangchera Puk of Mamit district offers a range of cave sensations because of its gloomy atmosphere, unique acoustics, distinct odors, tactile touch with terrestrial surfaces, and so on.

15. Pukzing Cave

Indeed, “A Cave of Shouting Stone” in the Mamit district. It consists of three chambers, each measuring around 4 square meters and connected by tiny tunnels.

16. Phulpui Grave

Phulpui tombs are a prominent tourist destination in Mizoram. Similar to the Taj Mahal, this cemetery has a timeless love story woven within it. The Phulpui tombs are located in Mizoram’s Aizawl district. The primary attractions here are the two tombs and the tale that surrounds them. These two graves stand close to each other, narrating the story of eternal love. According to folklore, Phulpui village head Zawlpala married the mythical princess Talvungi of Thenzaw. Talvungi later married the chiefs of Punthia and Rothai, as polygamy was common at the time. However, she was unable to give up her love for Zawlpala.

Upon discovering his demise, Talvungi goes to the village and digs beside Zawlpala’s tomb, seeking assistance from an old woman to end her own life. Today, these cemeteries are a must-see tourist attraction in Mizoram.

17. Bengkhuaia Thlan

Bengkhuaia Sailo, the chief of Mizoram’s Sailo tribe, is commemorated by this tomb that the people created. Bengkhuaia is thought to be one of the most prominent tribal leaders, having founded the first settlement in Thenzawl in 1863, when the area was still covered in impenetrable forest. During the early years of British forays to the Cachar highlands, the British soldiers frequently clashed with the tribes that lived there. In one of these conflicts, in 1871, Bengkhuaia arrested Mary Winchester, a six-year-old Scottish child. Mary lived among the Mizo people for a year and was given the name ‘Zoluti’, ‘Zo’ meaning ‘Mizoram’, and lût meaning ‘enter.’ The British soldiers rescued Mary in 1872.

Historians regard this incident as a watershed moment in Mizoram history because it paved the way for the formal arrival of British settlers into the province. The tomb is among the most attractive and quiet spots in Thenzawl.

The Concluding Lines!

In a nutshell, Mizoram is a vivid tribute to rich history, culture, and artistry. Each landmark exemplifies the Mizo people’s fortitude and inventiveness, from simple bamboo homes to spectacular monuments such as Solomon’s Temple. The state’s distinct architecture and cultural attractions, such as the Mizoram State Museum and Mizo Hlakungpui Mual, present unique stories and honor Mizo heritage. Visitors to Mizoram discover more than just historical landmarks; they travel through the heart of Mizo identity, where tradition and modernity coexist. Mizoram’s landmarks provide a profound view into the heart of this northeastern jewel, allowing visitors to appreciate and honor its long-standing tradition.

If you haven’t read about the architecture of other Northeastern states (Seven Sisters States), then click the following links to read:

Assam

Arunachal Pradesh

References

- mizoram.gov.in. (n.d.). Typical Mizo Village. [online] Available at: https://mizoculture.mizoram.gov.in/page/typical-mizo-village-zokhua-falkawn-mizoram#:~:text=A%20typical%20Mizo%20village%20was,by%20the%20village%20elders’%20houses

- TripAdvisor.in. (n.d.). Mizoram Landscapes. [online] Available at: https://www.tripadvisor.in/Attractions-g297658-Activities-c47-Mizoram.html

- wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Mizoram. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mizoram

- everyculture.com. (n.d.). Mizo-Settlements. [online] Available at: https://www.everyculture.com/South-Asia/Mizo-Settlements.html#:~:text=Houses%20are%20constructed%20on%20raised,a%20thatched%20two%2Dsided%20roof.

- pphouse.org. (n.d.). Social Structure of Mizo Village: a Participatory Rural Appraisal. [online] Available at: https://www.pphouse.org/ijbsm-article-details.php?article=1231#:~:text=Houses%20were%20constructed%20on%20the,did%20not%20exist%20at%20present.

- nriol.com. (n.d.). Best Historical & Heritage Sites in Mizoram. [online] Available at: https://nriol.com/india-tourism/mizoram/historical-sites.asp

- medium.com. (March 19, 2024). Legacy of the Land: Cultural Monuments in Mizoram. [online] Available at: https://medium.com/@whitecamron596/legacy-of-the-land-cultural-monuments-in-mizoram-be6f41414bfe

![]()